The first time seeing the northern lights in my backyard on 3/23/23. Stunning.

Let me make something clear from the start: Sandra Allen’s A Kind of Mirraculus Paradise: A True Story About Schizophrenia really is a piece of anti-psychiatry propaganda.

The book opens with the author recalling how their estranged uncle, “crazy” Bob, had contacted them shortly after Allen had enrolled a graduate writing program. Upon learning that Allen is a writer, Bob calls them to say, “Hey, I wrote a book, man. I wrote the story of my life.” Not too long after that, Allen receives a bizarre manuscript from Bob in the mail, along with a note apologizing for its “messiness” and an offer to pay for Allen’s services. Of Bob’s typewritten transcript, Allen writes that it was “hideous to look at, even from a distance,” describing a “wall of text” in “almost exclusively capital letters, with no paragraph breaks” and “colons everywhere.” Allen thought it “stank like cigarettes.” Upon reading through several pages, Allen considered the possibility that Bob’s story might be a product of delusion or a calculated lie. Allen continued to read Bob’s manuscript, but when some of the language became “explicitly racist,” Allen chose to disengage. As Allen tells it: “I wanted to ignore it the way you ignore a urine-soaked pile of coats on a sidewalk or a man on a park bench screaming obscenities.”

AKOMP is not about schizophrenia, but about feeling toward schizophrenia. It’s is an experimental and contentious narrative, elegant in its execution and almost deficient in every other way. The author, Allen, an accomplished journalist and editor, takes on the topic of schizophrenia from an unconventional and experimental angle. The book oscillates between these two different narratives written in different fonts. In the first narrative, Allen tells Bob’s story. In the second narrative, Allen attempts to address larger issues pertaining to mental illness by investigating the conceptual and diagnostic meaning of schizophrenia, as well as the changing ways American psychiatry has treated madness. “I am no expert in so many of the complicated topics at hand,” Allen concedes early in the book. While Allen promises to vows to “compensate” by learning as much as possible, it quickly becomes painfully apparent that Allen hasn’t put in the research.

Allen’s own “reportage” on mental illness is dismal, unrigorous and tinged with a distinct moralizing anti-psychiatry ethos that bodes ill for the rest of the project. The book contains significant errors. The author’s reliance on several single-minded, simplistic talking-points mar what is otherwise an eloquent and entertaining experimental illness autobiography.

The first page of Bob’s manuscript, his own writing (in lowercase): “this is a true story of a boy brought up in berkeley california durring the sixties and seventies who was unable to identify with reality and there for labeled as a psychotic paranoid schizophrenic for the rest of his life.”

This theme of truth and veracity is invoked and reinvoked throughout the book. Allen recounts, somewhat regrettably, conducting a meticulous, fact-checking of her uncle’s story, including interviewing family and “comparing Bob’s facts with what I could confirm elsewhere in letters, report cards, resumes, and the accounts that people were giving me.” Allen’s investigation of the world around Bob strikes at the core theme of the book.

Allen seems to fear the delusion of Bob’s account of reality. And yet, Bob’s narrative is not where the careful reader should cast their suspicions. It’s Allen’s so-called “journalism” that has more in common with a Washington Post op-ed or Mad In America blog or Tom Friedman column than anything that is verifiable, fact-checked, and deeply committed to accuracy.

There are errors in AKOMP and they are chiefly mischaracterizations of medical treatment. Case in point, in a passage occurring about halfway through the book, Allen claims that psychiatric medications such as antidepressants and antipsychotics medication are “addictive” because “some” patients who “choose” to stop taking them often experience withdrawal symptoms.

Some people who’ve chosen to quit neuroleptics often find that comes with an excruciating period of withdrawal. Some feel that the addictiveness of these drugs isn’t sufficiently studied or communicated to patients.

In the passage above, Allen hopes you will conflate drug dependence and drug withdrawal with drug addiction and accept this unsubstantiated claim, which is a prominent talking point in anti-psychiatric circles, then assume that withdrawal from prescribed neuroleptic medication is just as harmful as someone withdrawing from heroin or opioids.

But let’s read this more closely and think about what is going on here. Allen is trying to convince us that prescribed neuroleptic withdrawal constitutes an “addiction” for those who choose to stop taking these drugs. Yet, drug dependency and withdrawal occur with many prescribed and legal nonprescription substances, sometimes resulting in “an excruciating period of withdrawal” for “some people.” Furthermore, if we understand the concept of addiction to involve some element of pleasure or positive reinforcement that leads a person to misuse or abuse a substance, it becomes even less compelling to argue that antidepressants or antipsychotic drugs are “addictive.” That’s not to discount the seriousness of withdrawal, which can certainly be “excruciating,” but they hardly fulfill addiction criteria. If I were to guess, however, I’d say that Allen is trying to push an anti-medication agenda, while appearing to offer a “critical” and “balanced” account of a complex topic. With the neat phrase “some people,” these words are divorced from their author and neutralized of their intent. It’s an incredibly irresponsible approach that Allen adopts throughout the project.

In another example, Allen unsubstantiated claim that “electroshock therapy” can cause comas should stick out like a thousand sore thumbs.

[Agnes] recalled hearing he had undergone electroshock therapy at Herrick Hospital. Gene wasn’t sure whether that was the case; Bob made no mention of it in his manuscript. (The controversial therapy can cause memory loss and comas.)

The parenthetical is key. A citation or example would go along way here. But Allen provides no evidence whatsoever, even anecdotally, that comas are a side effect of ECT. Probably because there isn’t any. While a cursory Google search on the topic came up empty, a colleague managed to find a single article from the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry reporting a case of coma occurring in a psychotically depressed man. But it wasn’t the ECT. Rather, the source of coma was reportedly due to the IV administration of droperidol during post-operative recovery. This article contains 9 citations and none of them lead to another relevant case.

It would be one thing if these two instances of unsupported and questionable examples of bullshit claims masquerading as facts were honest mistakes in an otherwise “true account of schizophrenia.” But, of course, they’re not. Other mistakes fall into two overlapping categories: poorly researching the issues and rhetorical strategies.

As Allen explained in one interview, an additional goal of this book is to successfully address bigger questions concerning mental illness, such as: “What is schizophrenia, what is mental illness? What is known about a category like schizophrenia and what is not known?” Compounding my discomfort with this book is the author’s superficial treatment of this topic.

Repeatedly, Allen writes of “some people” as if they are a meaningful metric. “Some people.” Who are they? No one knows. How many of them are there? Some. How many is “some”? 5? 20? 100? No one knows.

Some people feel that no amount of research will ever yield answers to basic questions about schizophrenia because the word ‘schizophrenia’ doesn’t refer to any actual disease. They argue that psychiatric diagnoses only reflect the biases of those giving them, whether individual or social. They point to antique diagnoses that, in hindsight, betray this phenomenon completely.

Certainly, the existence of multifarious reactions to the etiology of schizophrenia, the validity of the diagnosis itself, and the potential for research to find answers need no citation, but by offering zero studies, data, examples or empirical basis for such a claim, Allen’s statement is useless. Why is Allen writing any of this? What is the point? What exactly are we talking about here?

In my experience, people who’ve been psychiatrically diagnosed feel a variety of ways about their diagnosis and about the field of psychiatry itself. Some who’ve been told they have schizophrenia agree with the diagnoses, and some feel that psychiatric medication has saved their lives. Others of the opposite persuasion champion for the abolition of psychiatry entirely.

Allen engages in a false dichotomy, presenting the experience of diagnosis and of the psychiatric discipline as either cheerleaders of the life-saving benefits of psychiatry and, notably, psychotropic medication, or the opposing “critical” anti-psychiatry anarchists, who’ve read the writing on the wall, and seek to burn the psychiatric establishment to the ground. It’s an argument that don’t really need to “proven” or justified with evidence since it’s nearly impossible to argue with.

No two people I’ve interviewed or resources I’ve read about mental health care in America have felt the same way about what the right treatment should look like. But most everyone who follows these issues agree that the situation at present is quite grim.

You certainly don’t have to cite your own experience, but statements as abstract as this require context and elaboration. It should be easy to name one person among series of “no two people” and “most everyone.”

As some alternatives have taken root in this country in recent decades, others have worked to oppose them.

That’s great. But what alternatives are you talking about? Rhetorically, these “both sides” statements feel good on their face, even though they are intellectually vacuous. The problem is that Allen seems untroubled by and uninterested in the question of what, exactly, or how, or why this is occurring.

And, so, boringly, on. This book is full of silly arguments. If you’re sensitive to language, your eye and ear will snag on these statements. Their persuasive ability comes from their ability to sound plausible and intelligent and to be quickly forgotten about. It’s a manipulative way to write.

It’s sad because this book has moments of genuine eloquence. To be sure, the book is very personal, very well-written, but it’s also not very exciting. It’s actually quite dull. It’s worth asking yourself: what is Allen telling us here that we don’t already know? What have we learned?

Why should this matter? Because the value in Allen’s “true story about schizophrenia” comes from its power to nurture critical thinking and promote empathy among readers. Allen’s lack of rigor, care, and self-reflection betray an authorial intent that seems fueled by self-interest and exploitation rather than curiosity and care for people with severe mental illness. In this way, Allen’s project undermines both our understanding of schizophrenia and our ability to foster genuine empathy for people deemed to be a less-than-fully human threat to society.

If AKOMP had focused on Bob’s story alone, it would be have been an excellent contribution to the understanding of schizophrenia. So why did Allen step out of their zone of expertise to profile the meaning of schizophrenia itself?

It’s not my place to question the author’s emotional life, and it’s entirely possible that the mistakes made by the author are the result of misinformed or poor research, so let’s skip to another question concerning fact-checking: if this book was fact-checked, why are there so many errors? One answer is that Allen was intent on shoring up a conclusion they had reached well before they began their reporting for this book.

As it happens, Allen considers the kind of pre-mature conclusion bias in the context of making sense of Bob’s life story:

Had I read Bob’s manuscript only up to the description of his first stay at Herrick Hospital, I might have supposed it was a screed against psychiatry as a whole. Or that he disputed the idea that there was something going on inside his brain, something that made it hard for him sometimes. But his manuscript didn’t dispute this; perhaps it’s what he meant when he wrote on his manuscript’s cover page that he was unable to identify with reality.

Indeed, a troubling consequence of the author’s apparent anti-medication position is how it seems to be at odds with the reality of Bob’s life. By all accounts, Bob seems to have embraced medication and psychiatric care, even after experiencing violent and traumatic hospitalization. There’s no doubt about the horrifying description of Bob’s early hospitalization, where he was forcibly medicated and abused by staff. Still, he kept taking his medications, even despite the awful side effects. For instance, at the age of 55, Bob writes: “IM STILL ON MEDS, AS LONG AS THE GOV. PAYS FOR THIS SHIT, ILL KEEP TAKING IT.”

In another example, Allen lumps Bob in with “many people” who “call the diagnosis [of schizophrenia] itself as ‘label,’ a tool used to discriminate against, confine, discredit, and silence.”

Surely, as is clear from context, neither Bob nor Gene defined “label” as “a tool used to discriminate against, confine, discredit, and silence.” Indeed, I would argue that the average person (even “most people”) would understand “label” to indicate a name or category or classification that is someone attached or assigned to a person. This may not seem like a big deal, but I would argue that by overlooking this and letting it slide, the implication is that Allen is a better source, having already provided the word with a specific meaning—one that the reader is invited to fall back on. It doesn’t matter that Allen’s definition may be completely distinct from how Bob understands the term “label” – as a general name, classification, or category that is applied to something or someone, as is implied several pages later when Allen reports that Bob’s father, for whom the diagnostic category of schizophrenia carried little meaning, “also referred the diagnosis as a label.”

I find it oddly unsettling that Allen cannot – or will not – offer any satisfying explanation for writing Bob’s story. The most expansive answers come early in the book, when Allen expands on the process of translating or “covering” Bob’s manuscript:

I wrote my version of it, referencing his account as my guide. I kept going, really studying a chunk of his story and then writing it in a way that captured his spirit as vividly as I could.

Writing this way forced me to read his book closely, to try to understand every single phrase, no matter how seemingly unintelligible. Occasionally, I’d still decide that the way he’d put something was just too beautiful or funny or moving—or profane—to chance, and so I’d leave it his way. The capitalized words and phrases served as reminders, too, that this was someone else’s story.

Allen indicates that their they’ve “never had good answers” when asked what interested them about Bob’s story. It seems like an important question. Allen suggests that a “more interesting question” is why they kept writing, not why they began in the first place. It feels like a fatuous question designed intentionally bring about a particular kind of reading (or misreading). Put differently, Allen’s suggested question seems designed to protect the text from close reading. I could be wrong.

Allen also doesn’t reflect on the ethics of appropriation or their rights to claim authorial control over a story that’s not their own and without the permission of the original author. Allen doesn’t reflect on the representational politics of writing a story from a place of privilege about a topic which with they are self-admittedly (and demonstrably) have little to no expertise in. The utter lack of self-reflection combined with several other things raises a profoundly important question: Is Allen the correct person to write this book?

Here’s my question: why is Bob not included as a co-author to this book? The bulk of the book is his story (as told by Allen). What’s the justification for such a glaring oversight? Allen doesn’t offer any satisfying answers. The best we get is an early passage, where Allen describes writing their version of Bob’s story, “referencing his account as a guide,” with the added assurance that they wrote the book “in a way that captured his spirit as vividly as [they] could.” Yeah, but how? Allen offers nothing.

Finally, did the following really happen?:

I am curious about one particular event from Bob’s life, which I must be honest, reads as being completely made-up. The event in question occurs during Bob’s awful hospitalization and comes after he describes a promise from his friend Bart that, when he was discharged, he would protest their treatment by “going to the press” and telling the world about the conditions of the hospital. The passage, which comes early in the book, didn’t raise red flags at the time since the reader accepts that some of what Bob autobiography entails may be fantasy given the nature of his state of mind. However, in light of Allen’s admission at the end of the book, where they expresses meticulous attention to the factual quality of Bob’s memoir by fact checking Bob’s life details, including his time in the military, where he went to schools, and even verifying his certificate in welding, and then following up all of that by comparing stories and notes with family, something about Allen’s acceptance of Bob’s story of watching television in the hospital dayroom only hours after Bart was discharged only to see his friend on the news, protesting the treatment at Herrick Hospital and speaking to a reporter. Specifically, Allen writes:

That evening Bob was sitting on the sofa in the dayroom. On the news, a big black guy surrounded by protestors was talking into a reporter’s microphone. It took Bob a moment to recognize Bart, in part because he was wearing fatigues, not pajamas.

What was Bart doing on TV?He was flanked by about twenty-five people. They were holding signs; one said SHRINMKS KILL: Bart was yelling something.

It seems relatively easy to verify if it did since it was a televised segment. And given that Allen later describes investigating Bob’s dog to make sure it was real and jokingly attempting to verify Bob’s story about meeting Kenny Rogers as a patient in a psych ward and playing music with him Allen describes reaching out to Rogers, but not getting a response, which conveys some degree of incredulity on Allen’s part, although they do not come out and explicitly express disbelief. This doubt is not present anywhere in Allen’s telling of Bob seeing his friend on television the very day he was released, keeping his promise and whistleblowing on the hospital. In fact, Allen seems to double-down by offering some plausible explanation, perhaps sensing that the reader may harbor doubts, Allen points out that: “The first antipsychiatric protests were held around then, in Berkeley and a few other American cities—which perhaps explains what Bob saw Bart participating in on TV.” For me, the disbelief is based on the wild coincidence that a psychiatric patient would be discharged and able to contact appropriate media people that day and be taken seriously enough to be put on television and then Bob, while locked up in a very rundown and by all accounts abusive psychiatric institution would be watching that television news station that evening at the same time. It just all seems so implausible.

In the previous post, I described an ugly knot of a study from 2017 that centers on how ordinary people, who self-identify with a bipolar diagnosis, narrate their identity and experience through personal blogs. In eight short pages, the authors manage to:

- Deny agency to research subjects with bipolar disorder

- Impose a narrative on every mentally ill person (we are not all the same)

- Present an argument that impacts access to care in a very bad and unethical way

- Claim to know about mental illness from the outside

- Prioritize their research over the humanity of their subjects and others with this diagnosis

Deploying a value-laden methodology, the authors mine, quote, and re-publish sensitive information from personal blogs written by members of a community of which they are not active participants, without informed consent or permission from the bloggers, and for which they do not provide deep context. They consistently choose to ignore the truth from their subjects who write about their life in intelligent, accessible ways that are also brave and resilient.

What makes this study egregious, thought, is how the authors claim expertise on bipolar disorder identity by reducing a complex diagnosis and illness experience to a trivial performance or commodity. For the authors, these bloggers are not just wrong. They lack legitimate grievances.

The authors advance simplistic, moralizing, and claims on their subjects’ motives and character that threaten their reputations, access to support, and increase their risk of harm. Their colossally superficial analysis presents them as weak and amoral people at best; deceptive drug-seeking malingerers at worst.

Rather, the authors gesture toward a mind-bogglingly anodyne debasement of the medical model brought on by mainstream psychiatry’s (increasingly transparent) collusion with “big pharma.”

What’s the point of this?

When I first became aware of this research via twitter, I was horrified. The ethical and moral void, yep. But it would take another month before I read the study for myself, followed by (at least) another month of thinking, reading, tweeting, and writing before I could begin to articulate the depths of my outrage.

Through it all, I’ve been consistently plagued by the same set of questions: Why this study was conducted? Who does it serve? How does its benefit outweigh its horrible ethics, lack of intellectual rigor, and insidious analysis? Is this scholarship?

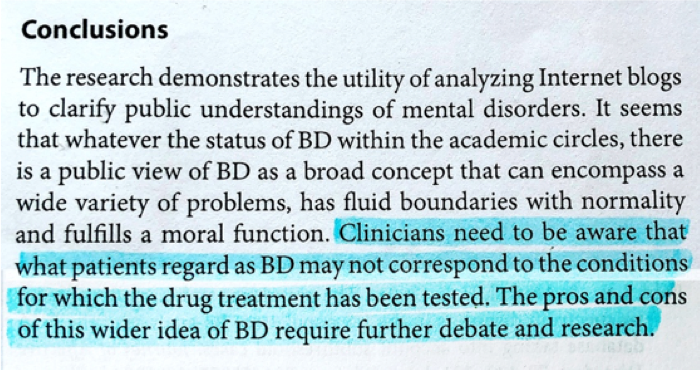

In the conclusion of the paper, the authors appear to offer a pithy justification for why this research matters, their most explicit articulation in the entire paper. They state:

“Clinicians need to be aware that what patients regard as BD may not correspond to the conditions for which the drug treatment has been tested. The pros and cons of this wider idea of BD require further debate and research.”

It’s worth a look at the second part of the authors’ claim, which informs the first: that “this wider idea” of bipolar disorder identity deserves “further debate and research.”

“The pros and cons of this wider idea of BD” is premised on bipolar disorder being a voluntary choice. The academic basis for such a claim aside, the authors make a leap from vague observations that their subjects’ narratives are: 1) “consistent with ideas presented on drug company websites,” and 2) “illustrate the attachment…to their diagnosis” to specific—and not explicitly hypothetical—instances of bloggers clandestinely deploy their diagnostic identity for personal gain (“mind-altering” psychotropics and/or money).

Clouded in academic trappings and qualifiers, the authors advance some toxic victim-shaming. The first claim (1) is too lazy to be examined in-depth. The second (2) is much more toxic and patronizing. Providing no evidence, even anecdotally, the authors suggest that bipolar disorder serves a “moral function” that enables sufferers to cling tightly to a diagnostic identity in such a way to cover up their personality flaws and legitimize bad character.

Which, of course, isn’t true. If bipolar disorder is being singularly attached to the subjects in ways that detract from their humanity, it’s because the authors chose to objectify them to tell a singular story. It’s a suspiciously paradoxical claim given the authors’ non-identitarian stance is built into this study. The authors literally designed their research in a way that enabled them to discard the author bloggers—compelling them to assume an almost organic and biological relationship with the media technology they used.

Which circles us back to the authors’ conclusion: the call for “further research and debate.” It’s an argument with a dead end, at the dead end before we even turn onto the road.

There are no “both sides” in a “debate” about whether people suffering from severe mental illness should be believed or exposed to harm with the people who are actively trying to harm them. There is only hatred and bigotry, which is rooted only in lies and misconceptions.

The Bad Faith of Liberal Academics

This study is bad politics and bad faith masquerading as “objective” scholarly insight—bolstered rhetorically via contradiction, sensible language, and the accoutrements of logical thinking. Instead of conducting rigorous scholarship research and attempting to locate a nuanced and more accurate “bipolar identity” in their subjects, the authors relied on value-laden reductionism and oppressive tactics to universalize a “truth” about the community this research is designed to support.

This is the danger when academics and intellectual elites, with all sorts of baggage, are allowed to lead and control radical movements. When the 1% of liberal psychiatry collude with an establishment ideology, radicalness is only aesthetic. Critical psychiatry is all talk and no action: bolstered by superficial social justice performances and neologisms, wherein the community they purport to care about are simply set aside rather than the very heart of the matter. It’s a movement that doesn’t challenge or change any of the underlying social conditions that lead to the acceptance of some people with mental health issues into public life and the criminalization and marginalization of other “less deserving” already oppressed folks.

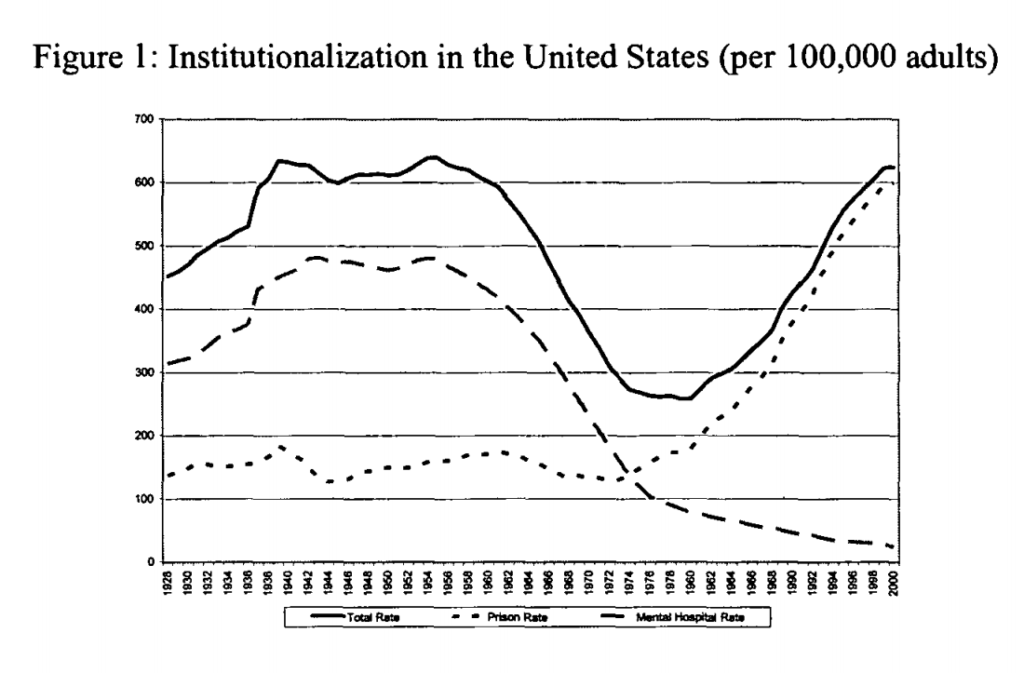

The most marginalized people with mental illness experience more extreme vulnerability, in part because more aspects of their lives are directly controlled by legal and administrative systems of domination—prisons, welfare programs, drug treatment centers, homeless shelters. These intersecting vectors of control make obtaining resources especially difficult, restrict access to zones of safety, and render every loss of job, family support, or access to an advocate or a mental health care more costly. At present, the dehumanizing cells of jails and prisons represent our de facto psychiatric institutions, the long-term psychological effects of detainment on migrant children, the ways in which structural racism and police-perpetuated gun violence exacerbate mental illness.

There’s something very paternalistic and liberal about saving mentally ill people from themselves instead of challenging supremacist institutions. In my mind, the most dangerous psychiatrists and mental health “experts” are not the Szaszian, in-your-face libertarians. It’s the deceptively benevolent ones who couch their ableism and paternalism in fronts of reason, science, faith, and with the guise of “opinion.” It’s centered on exceptionalism and privilege. It’s very Euro-American, it’s very Christian, and it’s very capitalist. “Happiness is a choice! Being negatively affected by racism, sexism, homo/transphobia and poverty are choices too!” Are we going to pretend mental well-being isn’t dependent upon often hostile environmental circumstances or just be reductive and ableist? If you want to put on a perpetually brave face, good for you. But let’s not pretend that regurgitating hypnotic Yoda pseudo-optimism bullshit is universal. As a person who suffers from debilitating depression that renders me non-functional, telling me “it’ll get better” when it’s looking bleak is the worst thing you could do.

Which is to say, if we actually care about justice then we need to find a way to discern people’s intentions before we accept their argument and research as valuable. Harsh as it sounds, there’s no doubt in my mind that the authors intended to humiliate and further alienate, exclude, and stigmatize people who wrote about their bipolar disorder as a legitimate medical condition that required psychiatric treatment via medication. Why? In order(?) to maintain their control over progressive movements, liberal elites must create a diversion to shift attention away from topics that might call on them to engage the messy work of real change. To maintain power, they have to appear busy. A common tactic is to fabricate a threat: perhaps a research study that’s more about separating out intended victims from unthreatened allies than anything meaningful. A red flag is when you find yourself asking, again and again: What’s the point of this? The authors often glide over the answer through rhetorical tics. Thus, they talk of a thing being a “concern” that requires “awareness” and “more research and debate.”

Drawing on my complex experience of “being bipolar” in addition to the original blogs written by the research subjects, I confidently state that next to nothing in this study is valid. It’s an ethical trashfire. I don’t get a choice about “being bipolar” so I’m stuck sharing an identity with the authors of the blogs. But that doesn’t mean I have to tolerate such a harmful study.

When it comes to “being bipolar,” one side is right, and the other side is wrong.

Telling me my identity is bad? Screw you – that’s not a neutral, unharmful opinion. Marginalized identities are not subjective, they’re not “opinions” to be politely debated by White liberal elite intellectuals. Words uttered and written about marginalized identities have an impact on their bodies.

That so many “experts” and academics—including a noted psychiatrist—think they’re qualified or entitled to (un)diagnose ordinary people with serious mental disorders based on a half-assed (or even whole-assed) engagement with a blog is even more reason not to trust anything in this study. No one is qualified to do this, no matter how much training they’ve had. You should be uncomfortable in the care of a mental health professional who has publicly demonstrated a willingness to judge someone, in aid of an ideology or in bad faith, who is suffering with a stigmatized disorder and has left digital breadcrumbs to their offline identity.

You don’t get to walk away from this kind of mendacity, no matter how important you are. Here’s why: it’s symptomatic of an institutional privilege and power whose checks and balances are sick, whose publication review processes are broken, and whose senior experts speak only in terms of what makes good or bad research without any reflexivity or ethical consideration.

Even if you choose to believe that the authors made all of these mistakes, not maliciously, but carelessly: it doesn’t make it any better. In fact, it makes it worse since it reveals a pattern, a habit, a system. The authors wrote with the easy knowledge that they would be believed, that theirs was the definitive and credible word, despite their distance and ignorance from the events in question. They wrote distracted, assuming no one who mattered was likely to question their account. (The bloggers would know the truth, of course. As would others with bipolar disorder. But no one told them about this study and even if they were informed, they have little ability or access to enter the conversation. They are effectively without the right to respond).

I imagine the authors will respond to my outrage in all or none of the following ways:

- Confusion: Why don’t I welcome minority viewpoints that challenge harm and coercion perpetuated by mainstream psychiatry?

- Dismissal: I’m not competent enough to know what’s best for me.

- Hostility: I’m brainwashed by Big Pharma or masquerading as mentally ill for my own personal agenda.

- Complacency: Continuing with what they’re doing because I can’t stop them.

I’ve seen this pattern before. But I should also add “But, academic freedom” and “You’re a conspiracy theorist” to the list to be safe.

Impolite Conversations

In the weeks I’ve been writing about this study, I’ve constantly worried about coming across as a respectful and serious scholar who demonstrates an appropriate “open-mindedness” in public. Gaslighting makes us question ourselves because we’re forced to entertain how academics and entire movements void us of our humanity and our capacity to define ourselves as equals.

The choice to engage in one-sided dialogue with power requires a lot of mental gymnastics. As such, there’s a tendency to self-police so as not to be too threatening, or an attempt to center and accommodate the feelings of the oppressor so that our humanity becomes easier for them to understand. I’ve written many drafts of this blog. It’s even easier to abandon a justifiably militant position in favor a more respectful one or silence simply as a means of coping over the seemingly never-ending demands for our rights to existence and freedom from violence.

But if we truly want less ableism and bigotry towards mental illness, we need to show that ableism and bigotry are unacceptable and beyond the pale. Civil conversations that concede virtually everything are not the way to get there.

There’s no justification for continually discounting the testimony of people diagnosed and/or suffering from serious mental illness other than to call it out as ableism and paternalism and question the motivations and credibility of the researchers who do this work.

Given what we know about this study and the authors, this is an easy call to make.

This research must not only be stopped; It must also be atoned for. The authors must acknowledge the harm they’ve done.

Why do they need to do this?

To be damn decent people for one. But in a practical sense: because people who identify as having a mental illness are the backbone of any meaningful understanding of where our problems started and what it will take to resolve them. And they don’t have a lot of our trust. Without us, the authors’ privilege will let them publish books and articles and secure speaking gigs, and be the face of a movement, but it won’t galvanize any actual action. It will generate personal power, but it won’t uplift the people they’re purporting to help.

Personal blogs are an act of communion, an act of humanity, the sharing of your story with another person. We each contain within us a private cosmos, and when we write ourselves, we make visible the constellations that constitute our experience and identity. However, there are many ways that these stories can lead to harm People who blog about mental illness are vulnerable to many types of harm, and unfortunately, sometimes those harms come from their “allies.”

Nowhere is this made more evident than in the article “Being Bipolar: A Qualitative Analysis of the Experience of Bipolar Disorder as Described in Internet Blogs,” published in the Journal of Mental Health Nursing in September 2017. This qualitative study—lead by renowned psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff with Anika Mandla and Jo Billings—analyzed a small sample of personal blogs written by self-identified bipolar disorder sufferers.

The authors in this study—authoritative, supposedly impartial and identity-less—undertook a thematic analysis of relevant material in personal blogs about the experience of bipolar disorder, including blogs from bipolar blogging networks, and critically examine the arguments used in support of and in opposition to mainstream conceptions based on the medical model. In reality, this research reflects a tremendously unethical, exploitative, co-option by the authors—insidiously occurring under the guise of welcoming and embracing knowledge.

Stories about mental illness belong to different domains of experience, but they have one thing in common: the people they belong to are seldom engaged with as authentic and credible thinkers, philosophers, or experts. While no means unique in its use of social media for data mining, this study functions as an up-to-date exemplar of vapid online research practices concerning marginalized groups.

Why “Being Bipolar” is Such an Unethical Study, And Why We Should Care

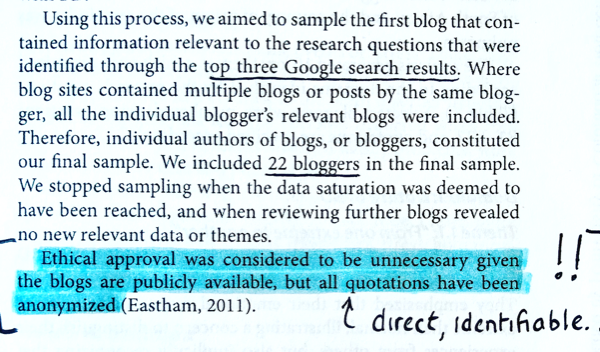

Let’s begin with the most succinct and disturbing sentence of the study which clarifies the authors’ cavalier approach to ethics:

“Ethical approval was considered to be unnecessary given the blogs are publicly available, but all quotations have been anonymized.”

As a careful reader, you might well be wondering how one can anonymize direct quotations, and the answer is: you can’t. There’s no such thing as an anonymized direct quote of an internet source. What the authors have done is merely produce an illusion of anonymity, and they’re done it poorly. The decision to pseudoanonymize subjects might be anodyne, but it also seems to indicate that the authors were not fully invested in their belief that personal blogs on mental illness are entirely of the public sphere.

There is much disagreement on whether content on publicly accessible personal blogs should be considered as freely available for any researcher to use. On the one side are those who take an almost laissez-faire view and see anything published on blogs as “fair game” for research purposes. Inherent in this view is the belief that authors have no reasonable expectations of privacy. On the other side are those understand that digital technology and culture have blurred the boundaries of privacy requiring more nuanced, fluid, and contextual conceptions.

The authors are in the first camp. They take an individualistic approach to privacy, despite the fact that, historically, socially, and politically vulnerable subjects haven’t been granted the same “right” to privacy as dominant groups—either offline or online.

They consider bloggers to be ultimate arbitrators of their fate, fully assuming all concurrent risks and potential harms that may come to them since they made the decision to post sensitive data in a publicly accessible space.

By this logic, bloggers with mental illness are not only responsible for paranoid caution and isolation from online communities, but the perpetrators (the authors) themselves bear no responsibility for predatory behavior. That kind of logic is how the criminal justice system falls apart.

“It isn’t the burglar’s responsibility for robbery if you didn’t exercise due diligence and hire a guard or invest in a security system.”

“We can’t try this murderer because you didn’t wear a bulletproof vest and helmet when you left the house this morning.”

The belief that individuals are responsible for the overcoming external harms levied against them is a theme throughout this paper.

The Worst Myth of Mental Illness

Running alongside this rejection of an ethical obligation to protect their subjects, is the authors’ sanctimonious, distorted, and offensive characterization of their blogs.

First up is the moralizing. According to the authors, a professional or self-imposed diagnosis of bipolar disorder is “real” in the biological sense but as functions morally in ways that enable “people to extrude unwanted parts of their personality into their ‘illness’.” In other words, when it’s taken up or diagnosed as a legitimate psychiatric disorder, “bipolar identity” is nothing more than a weakness of will; a crutch sufferers use to obfuscate “extreme, bizarre, usually dysfunctional and sometimes unfathomable manifestations of human agency.”

This is a bold and sanctimonious stance. The basis for a person’s character flaw? According to the authors, it can be gleaned by how bloggers attach themselves to their diagnosis.

The thing is, though, mentally ill people aren’t the ones making ourselves all about our illnesses. It’s people like the authors who choose to decontextualize and extrapolate from blogs about mental illness that make us all about our illness. In the context of this study, the experiences penned by bloggers who self-label with a “bipolar identity” are invented out of whole cloth, with no apparent connection to the circumstances of their lives—presented without race, class, gender, sexuality, or disability. The testimony of their lived experience is disembodied, decontextualized, and misrepresented by the authors with the assumption that these blogs reflect a consistent singular identity within and across bloggers.

Scientific Merit

Obtaining quality data and analyzing it properly is an essential component of ethically defensible research. Unfortunately, the authors seem to have gotten short with the truth and have interpreted bloggers’ words in value-laden and irresponsible ways.

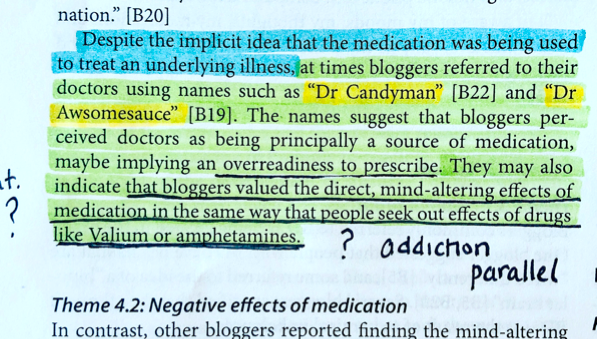

Consider the following interpretation, extracted from the paper:

“Despite the implicit idea that the medication was being used to treat an underlying illness, at times bloggers referred to their doctors using names such as “Dr Candyman” [B22] and “Dr Awesomesauce” [B19]. The names suggest that bloggers perceived doctors as being principally a source of medication, implying an overreadiness to prescribe. They may also indicate that bloggers valued the direct, mind-altering effects of medication in the same way that people seek out effects of drugs like Valium or amphetamines.”

Oceans of contempt and nonsense, all wrapped up in three sentences. I’ve read the blogs from which these quotes are taken and they do not “suggest” or “indicate” any of this.

The word “awesomesauce” (extremely good; excellent) was officially added to the Oxford English Dictionary in three years ago. Before that it held the same meaning as lighthearted slang. In the original entry, Dr. Awesomesauce exists in relation to Dr. Goodenough, and the author is hyperaware and concerned with being overmedicated. Of note, is the reference to an internalized stigma due to feeling like a “personal failure” for needing an antipsychotic.

While Dr. Candyman may seem like less of a stretch for describing an over-prescribing physician, the context of the entry is important. Here, the blogger is writing about two providers: psychiatrist (Dr. Candyman) and psychotherapist. More importantly, Dr. Candyman is described as providing helpful advice in finding a therapist. There is not a single mention of medication. The reasonable conclusion is this is lighthearted, sarcastic nickname for a medical doctor.

Let’s be absolutely clear about what’s happening here: the authors’ presented two bloggers’ nicknames for their psychiatrists and drew a straight line to a celebration of medication. This magnificently premature and misleading. They then make an interesting parallel to addiction and end with the conclusion that these bloggers may be opportunistic junkies.

The message is clear: these bloggers are manipulating a diagnostic identity in order to get drugs (which by their accounts made them feel terrible). We can take this even further to suggests that people with bipolar disorder disobey an authority and a legal system already in place to obtain “mind-altering” drugs that they don’t really need. The implicit assumption is that these bloggers might be criminals—in a judicial system already betrays people it purports to protect against racist, ableist, and classist favoring.

I am frustrated at the authors’ insouciance. Their cherry-picking for punctiform one-liners and contrived examples. These matter-of-fact assertions of less-than-obvious generalizations absent any elaboration are patterned in strange and increasingly troubling ways culminating into such a cataclysmically myopic paper. This is shameful. These quotations are embodied and situated in deeply authentic narratives that belie any of the authors’ defamatory and unprofessional interpretations/conclusions.

If you attribute an individuals’ character to her mental illness, you’re placing the responsibility for its existence squarely on her. It isn’t an oppressed person’s duty to survive and shoulder responsibility for mental illness. That idea itself is violent. However, the authors take their gaslighting much further by enacting violent and disciplinary reactions to their subjects.

Fake News

Donald Trump’s deployment of “fake news”—an abusive static logic that combines habitual lying, invalidation of trauma, a refusal to be held accountable for his statements, and skepticism of the media—presents a clear example of gaslighting in action. But Trump’s use of false rhetoric has been well-covered. More subtle yet nevertheless insidious is the gaslighting performed by the Moncrieff and colleagues, and those who defend their claims. The authors, for the most part, have been widely-revered by cis white middle-class Eurocentric circles, treated as renowned scholars, radical advocates, or personal heroes than the embodiment of harm.

The authors’ conviction that bipolar disorder is not only over-described and over-prescribed, but also not a “real” bodily illness at all, is a belief that brings them into direct opposition with the experiences of their subjects. Nowhere is this more apparent than the authors’ skepticism and credulity about the motivations of those who write about their experiences with mental illness (and blogging) is described in the following excerpt (emphasis mine):

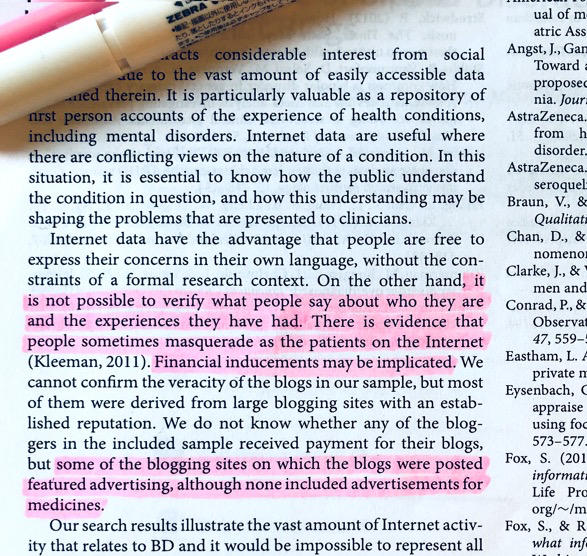

“Internet data have the advantage that people are free to express their concerns in their own language, without the constraints of a formal research context. On the other hand, it is not possible to verify what people say about who they are and the experiences they have had. There is evidence that people sometimes masquerade as the patients on Internet(Kleeman, 2011). Financial inducements may be implicated. We cannot confirm the veracity of the blogs in our sample, but most of them were derived from large blogging sites with an established reputation. We do not know whether any of the bloggers in the included sample received payment for their blogs, but some of the blogging sites on which the blogs were posted featured advertising, although none included advertisements for medicines.”

To sum up: they illustrate how well they listen to their subjects: the authors first suggest they aren’t even real people, then suggest they are acting deceptively by faking their distress for attention or personal gain (supported with a citation for an article on Munchausen syndrome, itself a psychiatric diagnosis for people who “play sick” for sympathy or attention). All the while, they cite the motive for profit as if to imply that writing deeply personal illness narratives on bipolar disorder blogging networks is a lucrative venture.

If the authors are studying the representation of “bipolar identity” on blogs written by self-described sufferers, then how are concerns on “fake distress” and “malingering patients” even relevant? For instance, even if a person is choosing a fictitious identity or creating a fictitious literary narrative, the desire is real and culturally significant. The authors seem to state this themselves in the next paragraph where they justify the importance of their research, as depicted below (emphasis mine):

“[S]ince the included blogs were easily accessed, whether or not they were genuine or representative, their content is important because it is likely to exert a disproportionate influence over public views.”

It’s one of many interesting contradictions and rhetorical moves in this study. These aren’t mistakes. This is deliberate and formulaic; they are following an unoriginal pattern of omission in order to misrepresent. Bourgeois academics like Moncrieff are deliberately vague, elaborating as little as possible and often time not at all. The contradictions are tactical and instrumental ways to direct a particular narrative. On the one hand, we’re meant to blame the bloggers for being manipulative and to sympathize with the authors (the obvious subtext). But the ending context about mental health stigma and discrimination was somehow not connected to the story at all?

The takeaway from this is for “normal” people to be skeptical of people with bipolar disorder for their “mental illness deception,” especially within a binarized and medicalized space, not a nuanced and balanced piece of straightforward reporting about blogs and identity. This is gross. This is harmful and amoral research that also lacks any validity or utility since the data analysis is inflected with the authors value-system.

Everything about this study is condescending and invalidating. The intellectual and practical dangers in this bootstrap rhetoric and moral model approach to mental illness reflects the same problematic logic of the medical model. They both employ the same oppressive logics to pathologize suffering and locate deviancy within an individual. Both perceive suffering and distress as “all in one’s head.” Both are harsh on the individual and soft on the social. This can be most clearly seen in the way the authors’ question the legitimacy of bloggers suffering: a move that only makes sense when you evacuate the politics of now from culpability and place the onus of well-being squarely on the individual.

What a lot of victim blaming and shaming people don’t understand is how mentally exhausting it is to never stop blaming yourself for your victimization. They don’t understand how terrifying it is to enter a space and be hyper-vigilant because you are solely responsible for the harm that befalls you. The internalized shame, guilt, and external shame that comes with consuming psychiatric medication is not unfamiliar to anyone with mental illness, including the bloggers under study.

At the risk of making this too much about me, I need to make my beliefs and reasons clear, such as they are (and were):

- I suffer from schizophrenia, or, as the authors of this study put it, “no I don’t.”

- I don’t like being spoken for.

- Whenever I hear the “mental illness is a myth” song, my ears shut down. I do not agree with the reasoning or the world view it produces.

- I do not believe that mental illness is a character flaw or a moral thermometer (but being sanctimonious and condescending toward people with mental illness/accusing them of faking for attention certainly is).

I know from experience that when I stop taking my medication I cannot function: I cannot move and no amount of validation, hugs, therapy, yoga, or aromatherapy can change that. That’s just me. I do not take my medication to get high; I just want to not kill myself. Like many people, I hate being on them. Relying on potent, mind-altering substances to function produces no small amount of shame, not to mention existential anxiety. I’ve tried to go off them many times in the hopes that the “real me” will finally be able to stand on her own. Each time, I run into the heartbreaking reality that my unaltered self is too painful to bear. This is not theoretical. I know this subject.

That said, this need to be said too: I’ve become perceptive to academics who appear to be doing the right thing while leveraging trauma for gain. Again, this is gross. And inexcusable.

Reimagining Ethical Research Online

There’s an urgent need to recognize the ways that we as researchers of vulnerable and stigmatized subjects reproduce and escalate harm and capitalize on (rather than care for) sensitive and identifiable data. This requires reflexivity at every step.

Water (and cats) flow into the shape of their container. And the internet has vastly changed the shape of the container. Our lives are contoured to the unique contexts into which we are born and reside which themselves shape our actions, emotions, and mindsets. Personal blogs and social media change the way we build relationships, share information, and make everyday decisions, including decisions about health and wellbeing.

It seems that many researchers want to find the “right way” to conduct research, by which they mean they want to check a bunch of boxes that will reassure them that it’s allowed and passable, without considering the possibility that maybe they just don’t do the research. There is a kind of colonial/white supremacist (and I think deeply patriarchal) stance which presumes that everyone ought to be able to study everything and I just think that all arguments that proceed from that premise are deeply flawed.

We need to understand that not every blog post or tweet is “for” us just because we can access it. We aren’t always the audience and therefore don’t always deserve extended explanations or history/context we’ve missed. When the content is of a sensitive or risky nature or involves marginalized identities, we need to consider whether we have a right to research at all.

Careful and respectful research can be done in ways that produce valuable knowledge, but they must foremost be motivated by an ethical commitment to participants and the desire to respect their knowledge and experiences. De-anonymization, the phenomenon of doxxing, harassment, and stalking are all live and urgent concerns on social media. It’s upsetting that our society and culture contains a seemingly endless supply of ways to make marginalized people feel unsafe and unwelcome. On the flipside, online spaces are emancipatory too. But it must be understood that public information exists in the context of power and consent, and we must construct our ethics in that context. The impulse, when an encounter between a human and theory goes badly, is to extract a lesson, but what moral can you draw from an encounter like this? That will be explored in Part 2.

Preface

(This is not going to be a very good blog post but it will be very long).

Why do people consider Derek Jeffreys’ book America’s Jails “groundbreaking” and “rich and thoughtful”? Why is it considered to be “a powerful condemnation of America’s jail system”? (This ebullient praise comes from two quotations on the back cover by reviewers who I assume either share the same fanatical politics as the author; or didn’t bother to read the book).

I find it disgusting, and I think this is the best thing you can say about it: this book should have never been published. In a disjointed fumble of personal anecdotes, aggressively irresponsible rhetoric, and hollow philosophical analysis, Jeffreys has written a book that centers the redemption and goodness of the cops and prison guards who harm as opposed to their victims. It’s a book that doesn’t even try to hide its white nationalism.

The fact that it’s so terrible in all possible ways – quality, politics, ethics – can’t explain why it was published by New York University Press as non-fiction polemical “alternative criminology” book alongside such luminaries such as Michelle Brown (The Culture of Punishment, 2009) and Judah Schept (Progressive Punishment, 2015). For this reason, it’s worth examining the sophisticated and concerning methods employed by this book in some detail in order to de-mystify—that is, to lay bare, the underlying ideological terrain.

Coping to Some Personal Bias

I wanted so much to like America’s Jails – nay, love it unabashedly. I chose to review this book, based on the descriptive blurbs from the author and publisher; I didn’t privately contain my excitement when I finally received my free copy from the publisher. The topic is close to my heart.

Inevitably America’s Jails sent me on a trip down memory lane. As it happens, I have passed through courtrooms, jails, and forensic state hospitals on my way to who I am today. I have known—personally and intimately—women (and some men) who live their entire lives with one foot to either side of the law. And, in my mind’s eye, I can envision voiceless and despairing people—perpetrators and victims alike—who would hope that a book claiming to “center their inherent dignity” to “shift public perception and understanding of jail inmates” by “highlighting the experiences of inmates themselves” would, well, actually do that. The result did not just disappoint me, it triggered my moral aggression.

Notes on America’s Jails1

My review of this book will be published soon on a website that’s not mine and have decided to post my many, many notes of this book so as to cover my ass lest anyone choose to accuse me – a lowly independent scholar – of being unfair or unrigorous in my critique of this book and the author who wrote it. I am very scared of being wrong here therefore I am dumping a lot of stuff here – in way too much detail – for the purpose of being respectful, comprehensive, and precise.

These notes are divided into sections and do not follow a continuous narrative. I’ve tried to organize everything as logical as possible – in an order that is, more or less, global to local.

- Not-So-Good Intentions

- Conceptual Framework

- Close Reading: Perspective and Representation

- Reparative Reading

Not-So-Good Intentions

This book raises key issues related to authorial intention (political motivation, personal involvement, questionable morals) and the narrative reliability (lack of expertise, unmet promises, false premises, inaccurate representation of fact and fiction).

In this section, I will begin with an attack on the author’s ethics by suggesting his repugnant political and religious motives have produced a book that best belongs in the genre of “fake news,” as defined by Jeremy Geltzer to mean “the publication of knowingly false, deliberately misleading or purposefully manipulated content intended to influence the recipient of the information” (2018, p. 298). The basis for my claims are anchored in a detailed examination and close reading of book – paying attention to methods, style, form, evidence.

About the Author

Jeffreys’ education and professional background is highly relevant to his writing in this book.2 According to his personal website, Jeffreys currently holds the title of Professor of Humanistic Studies and Religion at the University of Wisconsin, Green Bay. He has a PhD in “Religious Ethics” from the University of Chicago Divinity School. However, more interesting is Jeffreys’ undergraduate degree, earned from the University of Chicago in 1987, in a then brand new major called “Fundamentals: Issues and Texts.” Co-founded by Allan Bloom, Leon Kass, and James Redfield, this self-directed program (which is dubbed “fundies” by those in its inner circle) was designed to allow students to research fundamental questions about human existence (e.g. “what is freedom?”) or phenomena such as “what is the purpose of jail?” (which happens to be the eponymous second chapter of Jeffreys book) that held personal interest for them and then spend the next four years seeking answers through a handful of readings of a handful of classic texts of various genres (literary, religious, historical, and philosophical) that were informed by similar question. Outsider of the academy, Jeffreys spent time in the US Army. He has also spent a decade volunteering in prisons and jails throughout Wisconsin, both in the prison chapel and also teaching prisoners “about religious and philosophical topics like evil, anger, and love” (p. 4).

Intended Audience

The back cover tells us that it “aims to shift public perception and understanding of the jail inmates to center their inherent dignity and help eliminate the stigma attached to their incarceration.” I take this to mean that it’s intended for a wider (and whiter) audience of policy makers and the public alike, particularly in a political environment favoring privatization.

Faux Reform

America’s Jails is a form of faux reform that, on the surface, looks promising, but upon closer reading, reveals the author’s deep unwillingness to challenge the existing system. Throughout the book, Jeffreys masquerades as a progressive scholar making a progressive argument by deploying the very same talking points of faux progressive politicians who advocate for criminal justice reform but also seek to fund new jail projects.

In a context where “criminal justice reform” has solidified into a bipartisan issue; becoming trendy enough to be officially endorsed by our very own white nationalist and rapist in a sagging spray tanned pig skin president, there is a new wave of “faux reform” or faux progressive writing creeping into the conversation that, on the surface, seems to be promoting social justice measures but is actually nothing more than old wine in new old bottles. Jeffreys narrow focus on reforming jails does nothing to address the racialized violence of policing nor the structural racism, poverty, and economic violence that produce mass incarceration. Furthermore, Jeffreys’ focus on the structural internal conditions of jail – filth, ugly buildings, broken toilets, lack of beds – combined with concerns about overcrowding provide a perfect foundational argument for advocating for more jails, not fewer. Importantly, this is antithetical to Jeffreys claim that jails are morally unjust but a tragic fact of life (a belief that should be questioned and, ideally, resisted at all costs). But even if the author is acting in good faith: that he does believe jails are morally unjust but a tragic fact of life in order to protect society from the most dangerous and evil criminals; for Jeffreys these are probably serial killers but his focus in distinctly on rapists, child molesters, and domestic abusers. But this is a position that the majority of society, liberal and conservative alike hold – and therefore his argument, at best, suffers from a lack of imagination and resigned hopelessness, what on earth are we to make of an argument that mirrors the very same talking points of many conservative proponents of “bipartisan criminal justice reform” who seek to fund new jail projects by focusing on the conditions of jail, emphasizing the need for improved conditions for those living inside.

The clearest evidence that this book is a fake thing pretending to be real is to look at the policies that Jeffreys proposes. So, what exactly, is Jeffreys seeking to reform? In Chapter 5: “What Can We Do? Responding to a Crisis,” Jeffreys introduces what he considers essential responses that warrant immediate implementation to our “broken system,” including attention to:

- Pretrial risk assessment

- Money bond reform

- Use of force policies

- Improved mental health intake procedures

In other words, his focus in this book is on jails which makes sense given the title. Yet, for a book called America’s Jails, Jeffreys betrays a remarkable lack of understanding about them. In fact, the book’s promising title and aims as laid out on its back cover and within the introduction are completely nullified by the authors’ motives and intentional misrepresentation of jails in a way that mystifies their connection to a larger system of mass incarceration. In other words, Jeffreys conflates mass incarceration and jails routinely – at the same time, he makes technically true and important distinctions between jails and prisons which operate differently – especially in regards to money bond and mental illness (although, this is less the case when one considers how that prisons are also handling their own mental health crisis). What Jeffreys gets wrong about jails is crucial – failing to ignore their connection to a larger system of mass incarceration – which includes state and federal prisons and immigration detention facilities; all of which are inextricably tied to traditional policing.

On some level, Jeffreys knows the distinction between jails and prisons doesn’t matter since he routinely uses the term “prison reform” in the context of his argument about jails. But his proposed short-term solutions apply exclusively to US jails, which exclusively target pre-trial practices and the money bond system, oversight and procedural tweaks including improved intake procedures for mentally ill inmates and strongly worded guidelines about staff violence from the Department of Justice that “prohibit the use of force as a means of retaliation, control of movement, or punishment” support the “timely reporting of inmate abuse.”

Most appallingly, Jeffreys insists that systematic abuse and violence against prisoners in jails must be fixed through “greater jail monitoring, more federal oversight of jails, investigative journalism, and legal challenges from organizations like the ACLU” (p. 13). At the time this book was published, the DOJ was being run by Jeff Sessions, an ardent supporter of harsh sentencing policies, expanded incarceration, racial profiling, and unbridled police power. Jeffreys doesn’t mention any of this or bring up the politics of the current administration or the fact that the Department of Justice for whom he advocates to oversee his short-term solutions. This is all intentional. Jeffreys wants the reader to think he is above petty fighting among “political pundits” on both sides of the aisle. But his anti-politics are actually much worse than that: fanatical, orthodoxical, right-wing, evangelical, and scary as hell.

That Jeffreys frames his short-term solutions as being valuable for their ability to illicit broad political support (p. 11) is a big red flag that doesn’t bode well for any social justice approach, particularly now when we are contending with a rapist in the highest office and another on the supreme court; both of whom rose to power on a wave of right-wing populism defined by a toxic blend of White nationalism and racialized rage. Still, Jeffreys insists that there are deep divides among the political left and right when it comes to this topic. This is a bold faced lie. We can be generous and assume he is (a) delusional and uninformed, which may work since he does admit early in the book that he does not follow these debates closely, which begs the question of why he is writing a book about subjects matter that he is only tenuously familiar with and also telling the reader that he holds all the answers. Similar to Trump, a lot of what makes this book hard to read and also difficult to address is how contradiction and inconsistent it is.

Faith-Based Initiatives

The type of bipartisan reform being pursued by Jeffreys is inextricably tied to the 1990s “welfare reform,” which say “both sides” of the political spectrum coming together in an effort to overhaul a complex system. Of particular relevance, this period say the implementation of faith-based initiatives that resulted in many government-operated welfare programs being replaced by conservative Christian organizations. These initiatives also had criminal justice components, as noted by Kay Whitlock. For example, in 1997, the global prison ministry, Prison Fellowship – which has since become one of the largest programs of its kind – became involved with an evangelical residential pre-release program. Since then, there has been a rise and institutionalization of faith-based ministries in US jails and prisons. Moreover, states began allocating money to these private groups for Christian-centered faith-based programs in jails and prisons. According to Whitlock, these new streams of funding have “justified deregulation on the basis of religious freedom.” Thus, attendant with the agenda of “faith-based” corrections is a lessening of government responsibility for social welfare and an attribution of immorality as the ultimate causes of poverty and crime.

I am not an expert on this matter, but a quick cursory google search of “faith-based prison reform” brings up a page from the Charles Koch Institute for a session that includes CEOs and Executive Directors of the Justice Fellowship and Faith and Freedom Coalition. Just skimming, the phrase “human dignity” jumps out and feels, gut level, very parallel to this book.

I have a theory regarding Jeffreys’ personal involvement… I for one would like to know the nature of his volunteer work in jails and prisons for ten years. I originally assumed it was through his university, but I have a feeling it is with a for-profit faith based ministry. Disclosures of that nature are critical in a book about ethics. If I am right…

Conceptual Framework

America’s Jails belongs to a class of books that carefully straddles the line between two different meanings. The result is essentially two different books: one that claims to center the humanity and dignity of prisoners and one that illuminates their pathological criminality through the emotion of disgust.

- Double Concepts: Dignity and Disgust

- The Objects of Disgust

- Conceptual Incoherence

- More Disgusting Stuff

- Final Comments

Double Concepts: Dignity and Disgust

Just as this book is not really about the lived experience of prisoners, it’s also not really about dignity – at least not as it contributes to the stigmatization and dehumanization of its prisoner victims.

Long Story Short: America’s Jails renews a controversial philosophical debate concerning the function of disgust an indicator of a deep moral response by using jail – and, by extension, the prisoners inside – as philosophical tools to re-center the humanity of the author as well as the humanity of prison guards and cops who enact political violence against the vulnerable.

In this book, Jeffreys proposes an ontological shift, a new orientation toward old values that mirrors American and Puritanical tradition by linking an ideal concept of “human dignity” to the power of the “affective sphere” to insist that “negative affective responses” such as disgust (and its kin: contempt and fear) are highly cognitive emotions that play a central role in our societal impulse to stigmatize and dehumanize current and former prisoners. That is, prisoners are dehumanized – stripped of their personhood status and rendered objects or things because of (a) the ugly aesthetics and horrific sanitary conditions of jails; as well as their “spoiled identity” (á la Goffman) via their status as “criminals.”

Jeffreys insists that the disgust of jails – the degrading living conditions – and the contaminated status of prisoners “naturally” breeds contempt for them by prison staff and the rest of society. Contempt is defined as the experience of feeling “superiority over the disgusting object” (p. 108). In a complete lack of political ethics, Jeffreys argues that reflexive disgust leads to the systemic physical and psychological violence directed at prisoners by cops and guards. Basically, prison personnel abuse, neglect, and murder prisoners because they are disgusted by them and this disgust is completely natural.

It’s a disgusting argument.

But it’s not only disgusting because Jeffreys provides no sustained analysis of the operations of dignity and disgust that would help to convince the reader that these concepts would be ethically directed at protecting the dignity of prisoners than weaponized by those in power to maintain a culture of abuse and degradation against unpopular people who make them uncomfortable; it’s disgusting because of the remarkable ease it so perfectly crystallizes every revolting thing about this book that belongs in a moral landfill twenty thousands leagues under the sea.

The ease between disgust provoking contempt and anger toward the most vulnerable is not only a discursive mark of being dangerous, but also a very dangerous position in which to be. A loss of dignity transforms prisoners from people who possess an inherent goodness with unique capacity for growth and “transcendence” into objects or things that are susceptible to coercion and control and violence. The message is clear in context: the conditions of jail deny human dignity; foul odors, filth, loud sounds, exposed, malfunctioning toilets, overcrowding, lack of facilities, shortage of bed, ugly buildings, rodents, sick prisoners, bodily fluids, bad smells, loud noises. Within the jail, prisoners are non-people, monsters who must be defended against. Therefore, any violence from these non-people must be mitigated and defended against through the use of force given their dangerous status and is therefore justified in the name of public safety. I’m not sure that makes sense but the point I am trying to make is that Jeffreys has set-up a conceptual framework that essentially “traps” prisoners into a state of perpetual thingification. The key to doing this, I think, is by refusing to blame or hold accountable the cops, guards, and staff who assault and neglect prisoners on a daily basis. The only way Jeffreys can do this is by making an argument that their violence is somehow “natural” or beyond their control.

Definitions:

What is Dignity?

Dignity is a thorny concept. Jeffreys defines an ideal of dignity as the “value of a person” (p 79). What is a value? “Values are what attract us and gain our attention” (p. 79). So, dignity has something to do with values, which are whatever the what that attracts us to another person is.

At the same time, Jeffreys invokes the same term, but time as a verb, to show us how to value someone else’s dignity. In particular:

- “[w}e ought to be attention to the inner lives of those we confine and consider how our practices devalue their individual identity” (p. 96).

- “[w]e should refrain from treating them merely as things or commodities” (p. 97).

Then, to value someone’s dignity involves recognition of their “inner life” – their individual identity – which is presumably accomplished partly by not “thingifying” or commodifying them. And yet, Jeffreys clearly hasn’t done the reading since within the prison industrial complex, prisoners are commodities just like computers and corn are commodities.

As we read on, we learn that we possess dignity “because of our reason and autonomy…and our transcendence in relation to values” (p. 82).

I am not clear on what “transcendence” means and Jeffreys doesn’t provide a clear definition. It seems super religious-y. In my mind, I have been thinking about it as a vague destination that comes from “growth” – whatever that might be. However, we learn that inherent human dignity is tied to rationality and our capacity for self-determination.

Which…is interesting given that incarceration, by definition, removes individuals from the autonomy of their private lives and places them at the mercy of the state for the purposes of punishment. Incarcerated people, therefore, are completely reliant on the state to meet their basic needs. In the absence of the fulfillment of those needs, illness, pain, or even death can result. Jeffreys doesn’t address any of this.

Moving on, Jeffreys draws inspiration from Erving Goffman’s notion of stigma as a “spoiled identity.” Jeffreys tells us that “[s]tigma involves a failure to recognize a person’s individual identity” (p. 102). Furthermore, we are told that we can know perfectly well that a person has dignity and still stigmatize them. How so? Because the ugly aesthetic and degrading conditions of jails fuel “negative affective responses” like disgust, contempt, and fear “blind” people including prison guards and staff to a prisoner’s inherent value as a person.

In a complete lack of political ethics, Jeffreys invokes an ableist concept of “value blindness,” which he defines “an incapacity to recognize the centrality of a value” (p. 100), to argue that “disgust and contempt lead some staff to abuse inmates” (p. 100).

This wasn’t the book I wanted to read. I certainly wasn’t expecting a “captors don’t abuse vulnerable bodies, philosophical concepts do” argument. To be clear, I think this is a ludicrous load of ideology.

The Objects of Disgust

No other part of this book makes me sigh and give up faster than the conceptual “bit” — which, to be completely clear, is saying something. I confess, to begin, that I cannot get a firm grip on how all of this works, or what the hell is going on philosophically. So, I am least confident – and least motivated – to untangle this mess. But, that said: I am confidently sure this is all garbage.

The primary emotion featured in text is disgust.

Definition:

What is Disgust?

Jeffreys defines disgust as “a reaction to something we think is contaminated and inappropriately located,” arguing that disgusting objects “often culturally-specific, and include putrified objects, insects, bodily secretions, dirty bodies, kinds of foods, and forms of sexual activity” (p. 100). Here, he seems to conflate conditions characteristic of the contemporary world with conditions common to all human societies.

According to Jeffreys there is also a moral component to disgust that relates to the topic at hand since “we find vices and crimes disgusting” (p. 105).

Jeffreys provides the example of child molesters and how “many” people find them and their crimes disgusting. In addition, Jeffreys notes how in the past, many have also found certain groups disgusting, writing:

“This deeply problematic kind of disgust often persists despite arguments demonstrating its irrationality. For example, disgust at Jews in some societies has often endured despite its unethical and irrational character” (p. 105).

Jeffreys’ approach to “ugly” emotions and their “objects” is inextricably tied by to the early 18th century “realist phenomenology” of Very Catholic philosopher Aurel Kolani. According to Kolani – and, by extension, Jeffreys – “negative affective responses” are the means by which the human mind apprehends certain qualities about the world, most importantly, those qualities that pertain to the (dis)value of objects. The primary emotion discussed by in America’s Jails is disgust. Emotions also have intentionality since they “reach out” towards their objects. In this case, intentional does not refer to purpose or deliberate intent but rather to the fact that mental phenomena such as disgust, contempt, and fear are “about something”; they are directed towards some object or another. (So, if I am disgusted by spiders or prisoners or gay people, my fear is directed towards spiders, prisoners, and gay people, and they are its intentional object. Of course, all of this raises the question of whether people might set out to disgust themselves. Or whether any of this is universal.